Laser Safety

- Article Content:

In the early 1960s, the laser was an invention looking for an application. Not so any more today, lasers have myriad uses:

- Checkout counter scanners

- Consumer devices -- CD and videodisk players, laser printers, laser pointers, etc.

- Industrial -- imaging, welding, cutting, drilling, trimming, scoring

- Surgery

In other words, the laser now is a common tool. Like most other tools, lasers are capable of causing injury to their operators and others, if improperly used.

Elements of Laser Safety

Light

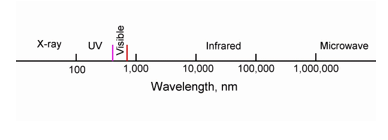

First and foremost, the laser is a device that produces light, hence the acronym LASER, which stands for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. The word "light" evokes in us thoughts of visible light, but most light is not visible: our eyes respond to only a narrow band of wavelengths, from about 400 nanometers (nm) in the violet, to about 760 nm in the red. Yet there is ultraviolet light (UV C wavelengths shorter than 400 nm) and infrared light (IR C wavelengths longer than 760 nm), which lasers and other light sources produce, but which cannot be seen.

Laser light

Laser light has several notable qualities, some of which are unique:

- Laser light is monochromatic, meaning that it is all of one wavelength.

- Laser light is highly directional, in a tight beam.

- The laser beam is highly collimated, i.e., very "parallel."

- Because of the directionality and collimation, laser beams can be very powerful.

- Laser beams tend to be small in diameter, often 1 mm or less.

The Human Eye

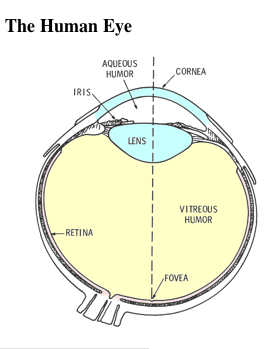

Let's look at the human eye: The cornea is the main focusing element, and the lens performs fine focusing duties. The space between the cornea and lens is filled with a watery liquid known as the aqueous humor, and the interior of the eyeball is filled with the jelly-like vitreous humor. The retina is the screen upon which the cornea and lens project an image of the outside world. The fovea is the seat of sharp vision. The retina is connected to the brain by the optic nerve. Signals generated in the retina are transmitted by the optic nerve to the brain, which interprets these signals as vision. The cornea, aqueous humor, lens, and vitreous humor are called the ocular media. They are the stuff through which light must pass to reach the retina.

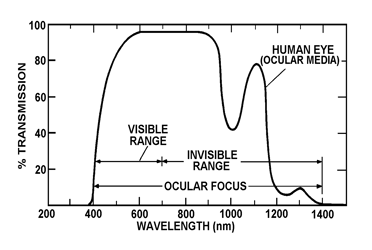

Obviously, light must reach the retina, and the retina must respond to it, in order for us to see the light. In order for light to reach the retina, the ocular media must be transparent to it. Here we see that the ocular media are transparent to visible light (surprise!).

The lens absorbs UV, and the older we get, the more the UV cutoff extends to the longer wavelengths. Babies and young children can in fact see a ways into the UV, but the lens yellows with age and by the time we are adults, most of us have lost that ability. UV lasers thus are not retinal hazards, although they can be hazardous to the eye in other ways.

But note how far the transparency of the ocular media extends into the infrared (IR) C all the way out to 1400 nm, in varying degree. The retina normally does not respond to wavelengths much longer than about 760 nm, so this light is invisible, even though it reaches the retina. This creates special hazards, which we will discuss later.

This wavelength region, 400 nm - 1400 nm, is called the retinal hazard region.

Laser Hazards

The rated power of a laser often belies the hazards of the beam. For example, to the layman a power of ten Watts seems trifling -- barely enough to make a night-light. Yet, ten Watts in a 1-mm beam provides an irradiance greater than a thousand Watts/cm2, which can ignite flammable materials and cause severe skin burns. If the wavelength of the light is within the retinal hazard region it can reach the retina of the eye, and the high degree of collimation, which is characteristic of a laser beam, creates a special hazard.

Recalling basic geometric optics, we remember that a parallel beam of light that enters a converging optical element, such as the cornea/lens focusing element of the eye, will be focussed down to a geometric point in the focal plane. This of course concentrates all the power in the beam into an infinitesimal spot, and results in an infinite irradiance.

The cornea/lens is not aberration-free, and there is diffraction from the iris, so the spot on the retina is not infinitesimal C but it is very small: in a well-corrected eye, a laser beam can produce a spot 20 :m diameter on the retina. Such a spot has an area about 3 x 10-6 cm2.

Thus, even a low power laser can produce a surprising retinal irradiance. Intrabeam viewing (i.e., the laser beam enters the eye directly) of a 1 mW (0.001 W) laser results in a retinal irradiance more than 300 W/cm2! Compare this to the 10 W/cm2 image of the sun on the retina of a person who views the sun at noon on a bright summer day.

The optical gain of the eye for a highly collimated beam, which is the ratio of the area of the retinal image to the area of the pupil of the eye, is 105. This is why lasers in the retinal hazard region are capable of causing retinal damage.

Damage Mechanisms

Although it is tempting to compare the focussing action of the cornea/lens to that of a simple burning glass, other mechanisms may damage the retina:

- Thermal

- Photochemical

- Mechanical

Thermal is easiest to comprehend, because it is like the burning glass. Simply put, the irradiance is so high that the illuminated area on the retina becomes overheated and a burn results. There is a threshold for this type of damage, and repeated sub-threshold exposures are not cumulative, provided the retina has time to cool between them.

Photochemical damage is more likely at the shorter visible wavelengths, peaking at about 440 nm. Repeated exposures within about a 24-hour period are cumulative.

Mechanical damage results from acoustic shock waves generated by very short pulses. Less is known about this mechanism, but research is ongoing.

It is important to realize that these mechanisms may act synergistically, in ways that are not completely understood.

Near-IR lasers, 760 - 1400 nm, present special hazards. These wavelengths are in the retinal hazard region, but they are invisible. Thus stray beams and reflections cannot be seen, and might be detected only as the result of an injury. Many serious retinal injuries have been caused by accidental exposure to near-IR laser beams.

Non-retinal Laser Hazards

The high irradiance or radiant exposure in an unfocussed laser beam can cause severe injury to the cornea and to other body tissues.

ADDITIONAL SAFETY RESOURCES

Laser Institute of America (LIA)

12001 Research pkwt, STE 210

Orlando, FL 32826

Phone: 407-380-1553

Toll Free: 1-800-34LASERAmerican National Standards Institute

ANSI Z136.1, American National Standard for the safe Use of Lasers

(Available through LIA)International Electro-technical Commission

IEC 60825-1, Edition 1.2

Safety of laser products -

Part 1: Equipment classification, requirements and user's guide.

(Available through LIA)Center for Devices and Radiological Health

21 CFR 1040.10 - Performance Standards for Light-Emitting Products

US Department of Labor - OSHA

Publication 8-1.7 - Guidelines for Laser Safety and Hazard Assessment

Laser Safety Equipment

Laurin Publishing

Laser safety equipment and Buyer's GuidesHaas Laser Technologies, Inc. recommends that laser users investigate any local, state or country requirements as well as facility or building requirements that may apply to installing or using a laser or laser system.

- Article Picture:

- Last Updated Date: 2025-02-06

- Hits: 672